In my earlier blog post on heutagogy and technology, I was very positive about engaging with Virtual Reality and creating a couple of VR experiences. I noted that technology, on this occasion, provided sufficient scaffolding for me to complete the task, and in that sense worked well with a heutagogical approach. The question implicit in the post was whether an extrinsically motivated learner would have had a similarly rewarding experience of heutagogical and technology working in unison to facilitate effective learning. Extrinsic motivation via external rewards can motivate one to complete a task, yet, unlike intrinsic motivation, it doesn’t last long (Serin 2018). (The video below tells a more complete story about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and that the combination of the two is necessary).

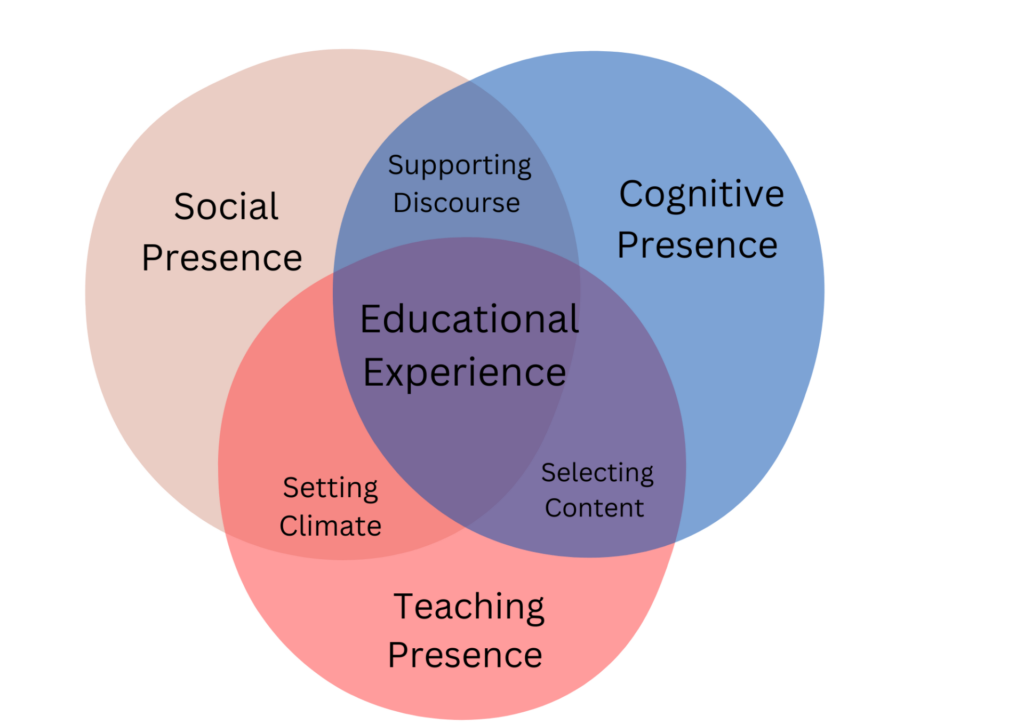

In contrast to my experience, Henderson, Selwyn and Aston (2017) found that students use technology predominantly for revision and consolidation purposes (e.g., replaying recorded lectures) instead of creative and participatory ways. I am not suggesting that students’ relationship with – and use of – technology haven’t changed since 2017 (the year the said study was published), not least because of the expansion of remote learning provisions during the COVID-19 lockdowns. However, what this study highlights for me is that technology in and of itself doesn’t create learning. My own experience of relying on technology for remote teaching over the last few years suggests that implementation of technology should be led by sound pedagogy. Creation of Community of Inquiry (figure 1.) requires the sort of teaching and learning strategies that should be present in every and any teaching and learning situation (be it online or in person).

For example, engaging students in asynchronous discussions online (not unlike in a physical space) requires an outcome-oriented task, explicit teaching of communicative strategies, teacher presence and clear expectations for participation (Verenikina, Jones & Delahunty 2017).

So, what’s special about technology? While technology may provide convenience and allows educators to roll out teaching and learning at scale, it also creates modes of surveillance. Over the COVID years, we’ve seen an explosion of learning analytics spurred by an increased use of Learning Management Systems (LMS) (Geisel, Warkentin & Snow 2022). Learning analytics capture students’ every move on the LMS. Surveillance in education is not new (Gillard & Selwyn 2022). Yet, having all this Big Data extracted from students should give us pause. It’s true there are applications of Big Data in learning that can contribute to improving student experience, but these benefits run up against the ethics of personal data (Clow 2013).

Let me return to the beginning of the post where I juxtaposed extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. In my earlier blog posts, I expressed scepticism about technology’s capacity to revolutionise education. Technology can sure be helpful, but technology alone is not a panacea for student disengagement. Technology may enable educators to learn more about their students in ways that are convenient and efficient (albeit not free of ethical ambiguity). And yet, figuring out what is really going on with student engagement, motivation, their interest in learning requires a different type of data gathering … and on that note, I will leave you with Michael Wesch’s reflection on learning and life.

References

Clow, Doug (2013). An overview of learning analytics. Teaching in Higher Education, 18 (6), 683–695.

Garrison D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: social cognitive and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11 (1), 61–72.

Geisel, J., Warkentin, H. and Snow, J. (2022). Ethical use of learning analytics for student support, not surveillance. Proceedings of Academic Integrity Inter-Institutional Meeting, Canada, 5 (1).

Gilliard, C. and Selwyn, N. (2022). Automated Surveillance in Education. Postdigital Science Education.

Henderson, M., Selwyn, N., and Aston, R. (2017). What works and why? Student perceptions of ‘useful’ digital technology in university teaching and learning. Studies in Higher Education, 42 (8), 1567–79.

Serin, H. (2018). The use of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to enhance student achievement in educational setting. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 5 (1), 191–94.

Sprouts (2021, March 1). Extrinsic vs Intrinsic Motivation. [Youtube video].

Verenikina, I., Jones, P. T. and Delahunty, J. (2017). The guide to fostering asynchronous online discussion in higher education. Australia: FOLD.

Wesch, M. (2016, April 16). What baby George taught me about learning? TEDx Talks.

Thanks for your blog post Elena! Your insights about surveillance in education and how technology enables this made me think of the current debate on proctoring software. Proctoring software is software that can monitor a student’s computer during an online test to detect cheating. Some proctoring software can even take a photo of the student during the test.

The use of proctoring software has been controversial (Khalil et al., 2022), with some people arguing that it invades students’ privacy and creates a hostile testing environment. Others argue that it is necessary to ensure academic integrity in online courses. I think the debate on proctoring software highlights the tension between the need for surveillance in education and the need to protect students’ privacy as well as ethical concerns: Is it ethical to use proctoring software? Is it effective? And what are the implications of using this software for the future of education? In my opinion, the use of proctoring software raises more questions than it answers, and I think it is one of many things that we need to be careful about as we move forward with technology in education.

Khalil, M., Prinsloo, P., & Slade, S. (2022). In the nexus of integrity and surveillance: Proctoring (re) considered. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning.

Thanks, Christoph, for engaging with my post. Yes, very much agree with your concerns around proctoring. This was very much at the back of my mind when writing this post. Gillard and Selwyn (2022) also talk about problems with proctoring — that’s one of the references in my post. I think, there is a concurrent conversation happening around student’s autonomy in assessment and moving away from closed-book exams.

Dear Elena,

Thanks for such a terrific and thought-provoking post! It touches on a lot of things I have been thinking through during this course as well, particularly the relationships between heutagogic learning, digital platforms, and ovearching pedagogy and learning outcomes. I like that your post calls for a balance between these areas, and that no digital platform provides a kind of panacea for students finding something relevant or engaging. While at first glance, this may feel dispiriting, it demonstrates the need to have the relationships between these areas to be an ongoing work in progress that as teachers we are always reflecting on and reworking, even in the moment as we’re teaching.

I really like your inclusion of the Community of Inquiry model, that encourages the fostering of cognitive presence, teaching presence and social presence. In my experience as an anthropology lecturer and tutor, different students with different learning styles will respond to each sphere – sometimes responding one week to a prompted cognitive reflection, and other weeks leaning on the social cohesion between students to prompt further learning reflection, or in other weeks rely heavily on the interlinked components on how the course is designed in order to know what to do next. It reminds me of how much these spheres are overlapping and interdependent (Fiock 2020, p 149).

While as a lecturer and subject coordinator, a lot of tutorial work for me is often delegated to tutors, it reminds me also of the importance of maintaining practice as a tutor as well as a lecturer when teaching social sciences. Tutoring a class as well as lecturing means that it is much easier to remain aware and responsive to ensuring the spheres overlap and interconnect, and that there is cohesion between heutagogic learning wider learning outcomes.

Thanks again for the great post – and thanks for the M. Welsch recommendation – I’ve always liked his work!

Regards, Rebekah

References:

Fiock, Holly S. 2020 ‘Designing a Community of Inquiry in Online Courses’ International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 21(1): 136-153.

Thanks, Rebekah, for engaging with my blog post. I do agree that proximity to students is necessary if one is to be responsive. Large-cohort teaching is very challenging in that regard. I am a fan of Wesch’s work, too.

Good post critiquing TEL Elena – totally agree that the key is basing learning design in learning theory and guided by design frameworks. I also agree that the focus upon using technology for proctoring is the wrong approach – we should be rather developing a culture of responsibility and ethical behaviour in our students rather than taking the easy way out though assuming everyone is cheating during our boring assessments!